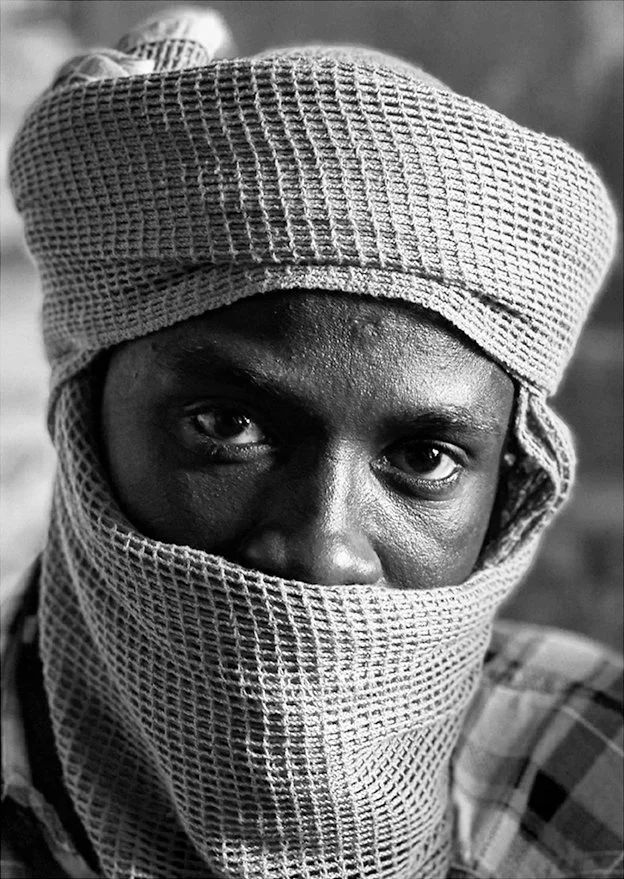

DARFUR

El cosmos interrumpido

Marwan Mohamed | Mohamed Zakaria | Abdelsalam Abdallah

25 octubre - 27 febrero

ES

Darfur explica el mundo. Adentrarse en su historia más o menos reciente supone penetrar en un microcosmos que sostiene un espejo frente a nuestros ojos y que muestra de forma cruda la naturaleza del ser humano, su relación con el hábitat, su psicología, los sistemas políticos, económicos y de poder que establece, y el efecto en todo ello de la perversidad, la contradicción, la esperanza y la resiliencia. Y también del sinsentido. Los tres fotógrafos de esta exposición nacieron en esta región al oeste de Sudán, a cuyas gentes se trata de rendir homenaje, aunque sus historias podrían ser de cualquier otro lugar, en cualquier otro tiempo pasado, presente o futuro. La muestra se conceptualiza y extrapola en el significado del cosmos de lo humano, que bebe de la explicación platónica del universo a través de sus elementos más básicos y simbólicos, del menos al más sutil: la tierra, el agua, el aire y el fuego. También el éter, como quintaesencia desconocida e hipótesis para el mundo: la esperanza y el futuro.

El cosmos en Darfur se ve interrumpido a varios niveles y el fuego de la guerra y la violencia se cuela detrás del elemento tierra para convertirse en destrucción y ruptura. Ya no es luz ni conocimiento y pone al resto de elementos a sobrevivir en torno a sí. Son estos elementos los comunes a todo microcosmos entendido como ser humano, y de ellos surgimos y con ellos convivimos. En Darfur se personalizan para marcar el destino de esta tierra y manifestarse, en sus formas más alegóricas y filosóficas, en cada individuo o colectivo y en cada historia. No parecía posible explicar Darfur en términos cronológicos o meramente sociológicos, su lección es universal y trasciende lo inmediatamente perceptible.

EN

Darfur explains the world. Delving into its more or less recent history means entering a microcosm that holds a mirror up to our eyes, starkly revealing the nature of humankind, its relationship with the environment, its psychology, the political, economic, and power systems it establishes, and the effect on all of this of perversity, contradiction, hope, and resilience. And also of meaninglessness. The three photographers in this exhibition were born in this region of western Sudan, whose people it seeks to honor, although their stories could be from anywhere, in any other time—past, present, or future. The exhibition is conceptualized and extrapolated from the meaning of the human cosmos, drawing on Plato's explanation of the universe through its most basic and symbolic elements, from the least to the most subtle: earth, water, air, and fire. Also, ether, as an unknown quintessence and a hypothesis for the world: hope and the future.

The cosmos in Darfur is disrupted on multiple levels, and the fire of war and violence seeps behind the element of earth, becoming destruction and rupture. It is no longer light or knowledge, and it forces the other elements to survive around it. These are the elements common to every microcosm understood as the human being, and from them we emerge and with them we coexist. In Darfur, they are personified to mark the destiny of this land and manifest themselves, in their most allegorical and philosophical forms, in each individual or collective and in every story. It did not seem possible to explain Darfur in chronological or merely sociological terms; its lesson is universal and transcends what is immediately perceptible.

CONTEXTO

Darfur es la zona cero del actual conflicto en Sudán, una lucha entre dos señores de la guerra y sus aliados arrasando a la población en pro de sus intereses. La situación parece haber sido la consecuencia de una profecía autocumplida que declaraba a viva voz y de manera repetida lo que bajo ciertos supuestos sucedía: los árabes se habían vuelto contra los zurga, o negros, siendo estos últimos los nativos y aquellos los colonos, según el paradigma que nació de una historiografía colonial sesgada y al servicio de legitimar sus acciones y su negligencia. Darfur fue un sultanato independiente hasta 1916, momento en que pasó a ser una provincia más del condominio anglo-egipcio sobre todo Sudán. Su etimología proviene de la palabra dar y fur, es decir, tierra o casa de la tribu de los fur, tal y como se denominaba a los habitantes de este territorio al oeste de Sudán.

Durante el sultanato se dio un proceso documentado de destribalización en el sistema de la posesión de la tierra y la gobernanza de la misma. El islam ofrecía un principio de solidaridad anclado en la idea de clan o ummah, comunidad islámica. Existió un orden supratribal que dio sentido a la centralización del poder, sobre todo durante el periodo de la llamada Mahdiyya entre 1885 y 1898, y el de colonización turco-egipcia anterior en los años veinte del siglo XIX. Se acabó con el liderazgo tribal y, por tanto, con la diferencia entre grupos. Los británicos colonizaron Sudán en dos fases que culminaron en 1922. Se reorganizó a la población en identidades estrechas y forzadas a través de censos y leyes de propiedad que rompían con el equilibrio previo y con el carácter puramente fluido de la identidad en Darfur. La principal y real diferencia era entre nómadas y sedentarios, categorización que dependía de la actividad a la que se dedicaban, cada uno compuesto por diferentes comunidades o grupos. Sin embargo, un grupo podía no dedicarse únicamente a una actividad ni en exclusiva ni para siempre, sin olvidar que cualquier conflicto entre comunidades se resolvía a través de acuerdos sellados por los líderes más respetados o a través de matrimonios entre miembros de diferentes grupos. La etnicidad se creó como herramienta política, no cultural. La etnia es una identidad política y una unidad administrativa para tratar de conseguir una paz barata y ficticia. La amenaza de ruptura de convivencia se consolidó cuando los británicos deciden que los no árabes, es decir, los nativos sedentarios, tendrían acceso a tierras (dar) y a participar en su gobernanza, a diferencia de los nómadas, de mayoría árabe. La tribu pasa a ser un concepto vinculado al favoritismo, a la discriminación y a la corrupción.

Son varios los antecedentes al conflicto de finales de los años 80, germen del que aconteció en 2003, y del actual. Entre ellos, un tema candente: la fuerte sequía en el Sahel iniciada en los años 40 y que desplazó el desierto del Sahara 100 km hacia el sur provocando que Darfur perdiera progresivamente un tercio de sus bosques, todo ello en un periodo de aproximadamente cuatro décadas. Se dio un movimiento migratorio masivo y el desplazamiento de las rutas nómadas hacia el sur a zonas de cultivo por lluvia. Ahora había menos territorio para más personas, y no todos los recién llegados tenían derecho a ocupar la tierra o tener acceso a ella. Por otro lado, el afán de crecer y prosperar desarrolló el mercado de tal forma que las granjas de explotación comenzaron a ocupar las rutas de los nómadas. Líderes como Nimeiry y Al Bashir fracasaron estrepitosamente en poner solución al sistema colonial de administración “nativa”, y el concepto de individuo tribal nunca evolucionó al estatus de ciudadano. Otro elemento primordial fue la guerra civil en el vecino Chad, que dio comienzo en los años 80 y que tenía un paralelismo casi literal con Sudán en las causas que bebían de la época colonial. Darfur fue utilizado por varios bandos y milicias como base de operaciones, quedando totalmente militarizado. En Darfur no había agua, pero sí armas, y a muy bajo precio, llegadas desde la Libia de Gadafi, que unió fuerzas con los nómadas camelleros, algunos refugiados y milicianos de Chad y después con el régimen islamista de Omar al Bashir, bajo el nombre de la Alianza Árabe, que disparó todas las alarmas entre los sedentarios no árabes y las fuerzas antigubernamentales de Darfur. Los aliados de estos últimos: las fuerzas no árabes de Chad de Hissan Habre, Francia, Israel, los Estados Unidos de Reagan y Egipto. Era esta una trama de guerras de proximidad en el contexto de la Guerra Fría. Las ideologías comienzan a forjarse al amparo de intereses económicos, colonialistas y de capitalismo extremo, bajo el disfraz de luchas étnicas.

Se formaron y consolidaron varios grupos rebeldes armados como el Movimiento Justicia e Igualdad (JEM por sus siglas en inglés). Y es en los años 80 cuando se empieza a oír hablar de los yanyaweed para referirse a milicias árabes de forma peyorativa. Era difusa la frontera que diferenciaba a estas milicias, formadas principalmente por nómadas, de los grupos de delincuentes y bandidos que se unían a ellas y causaban estragos entre la población bajo el beneplácito del Gobierno de Omar al Bashir, que los legalizará como Fuerzas de Apoyo Rápido (FAR) en 2013. Al Bashir creó un avispero en Darfur por estar lejos de ser una prioridad. Si la paz debía conseguirse en algún frente, este debía ser el del sur, con reservas de petróleo, cuyos territorios acabaron independizándose en 2011, naciendo Sudán del Sur como país. En el año 2000 se presentó en Jartum la primera versión del llamado Libro Negro [Black Book: Imbalance of Power & Wealth in Sudan], que reclamaba una agenda social que terminara con la desigualdad entre el centro y Darfur, totalmente marginalizado. El contenido no tenía que ver ni con lo étnico ni con lo religioso, pedían ser considerados ciudadanos con derechos y era generalizada la creencia de que el problema no eran los árabes de Darfur, a quienes consideraban tan pobres como ellos mismos, sino el Gobierno. Hubo numerosos intentos de paz entre los grupos rebeldes de Darfur y el Gobierno. Pedían ir en representación de la región al completo, no de un grupo étnico particular, para evitar que mermara su peso. Pidieron, a su vez, que se desarmara a los yanyaweed. Todo fue en vano. Ni la intervención de la ONU y la Unión Africana en las negociaciones dio resultado.

Se comenzó a coquetear con el término de “terrorismo” para hablar de los árabes de Darfur de forma generalizada, un término tan delicado como útil en aquel entonces: el contexto de la invasión de Iraq por parte de EEUU y sus aliados. La arabización de la violencia debe entenderse en el horizonte de “guerra contra el terror” en el que se enmarcó. Jamás antes se había dado unanimidad en el Congreso de los EEUU para declarar el genocidio en un lugar antes de Darfur. El debate semántico estaba servido y está, por desgracia, a la orden del día por el caso de la actual ocupación y destrucción en la Franja de Gaza. ¿Qué es genocidio, qué es guerra o crimen de guerra y qué es contrainsurgencia? Iraq, Darfur y Gaza entran en contradicción, los dos primeros en el mismo momento, Gaza después. La ley queda al servicio de la política, y quedará como un concepto diferente al de “responsabilidad de la comunidad internacional”. En palabras de Mahmood Mamdani, al hilo también de la reciente fundación de la Corte Penal Internacional en el momento: “Solo los crímenes denunciados por países soberanos son reales, pero el objeto del poder es transformar a las víctimas en proxys, cuyo dilema legitimaría la intervención colonial como misión de rescate”. Añadir que, de forma paralela, podían existir acuerdos que eximían y eximen a los países aliados y ricos de cumplir la ley inventada por organismos inoperantes. Declarar el genocidio en Darfur pudo ser una oportunidad para los poderosos al implicar la obligación internacional de intervenir. Dichas intervenciones pasaban por culpar solo a quien interesaba. La idea de impunidad entró en escena, y no nos ha dejado hasta nuestros días. El resultado real: la población de Darfur, y la de Sudán al completo, ha sido abandonada al caos y a la negligencia durante décadas.

CONTEXT

Darfur is ground zero of the current conflict in Sudan, a struggle between two warlords and their allies, devastating the population in pursuit of their interests. The situation appears to have been the consequence of a self-fulfilling prophecy that loudly and repeatedly declared what was happening under certain assumptions: the Arabs had turned against the Zurga, or Blacks, the latter being the natives and the former the colonists, according to the paradigm born from a biased colonial historiography that served to legitimize its actions and negligence. Darfur was an independent sultanate until 1916, when it became another province of the Anglo-Egyptian condominium over all of Sudan. Its etymology comes from the words dar and fur, meaning land or house of the Fur tribe, as the inhabitants of this territory in western Sudan were known.

During the sultanate, a documented process of detribalization took place in the land ownership and governance system. Islam offered a principle of solidarity anchored in the idea of the clan or ummah, the Islamic community. A supratribal order existed that gave meaning to the centralization of power, especially during the period of the so-called Mahdiyya between 1885 and 1898, and the earlier Turkish-Egyptian colonization in the 1820s. Tribal leadership, and therefore the differences between groups, were eliminated. The British colonized Sudan in two phases that culminated in 1922. The population was reorganized into narrow and enforced identities through censuses and property laws that broke with the previous equilibrium and the purely fluid nature of identity in Darfur. The main and real difference was between nomads and settled people, a categorization that depended on their occupation, each group comprising different communities or subgroups. However, a group could not dedicate itself solely to one activity, either exclusively or permanently, and any conflict between communities was resolved through agreements sealed by the most respected leaders or through marriages between members of different groups. Ethnicity was created as a political, not a cultural, tool. Ethnicity is a political identity and an administrative unit used to try to achieve a cheap and fictitious peace. The threat of a breakdown in coexistence solidified when the British decided that non-Arabs, that is, the sedentary natives, would have access to land (dar) and participate in its governance, unlike the nomadic, predominantly Arab, groups. The tribe became a concept linked to favoritism, discrimination, and corruption.

There are several factors that contributed to the conflict of the late 1980s, the seed of the 2003 conflict and the current one. Among them, a burning issue: the severe drought in the Sahel that began in the 1940s and shifted the Sahara Desert 100 km south, causing Darfur to progressively lose a third of its forests over a period of approximately four decades. This led to a massive migration and the shift of nomadic routes southward to areas more reliant on rainfall. Now there was less land for more people, and not all newcomers had the right to occupy or access the land. Furthermore, the desire for growth and prosperity developed the market to such an extent that factory farms began to encroach upon the nomadic routes. Leaders like Nimeiry and Al-Bashir failed spectacularly to address the colonial system of "native" administration, and the concept of the tribal individual never evolved into the status of a citizen. Another crucial element was the civil war in neighboring Chad, which began in the 1980s and had an almost literal parallel with Sudan in its root causes stemming from the colonial era. Darfur was used by various factions and militias as a base of operations, becoming completely militarized. There was no water in Darfur, but there were weapons, and very cheap ones, arriving from Gaddafi's Libya, which joined forces with the nomadic camel herders, some refugees and militiamen from Chad, and later with the Islamist regime of Omar al-Bashir, under the name of the Arab Alliance. This set off alarm bells among the non-Arab settlers and anti-government forces in Darfur. The latter's allies included the non-Arab forces of Hissan Habre's Chad, France, Israel, Reagan's United States, and Egypt. This was a web of proxy wars in the context of the Cold War. Ideologies begin to take shape under the protection of economic, colonialist and extreme capitalist interests, under the guise of ethnic struggles.

Several armed rebel groups formed and consolidated, such as the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM). It was in the 1980s that the term "janjaweed" began to be used pejoratively to refer to Arab militias. The line between these militias, composed mainly of nomads, and the criminal and bandit groups that joined them and wreaked havoc on the population with the tacit approval of Omar al-Bashir's government was blurred. The government would later legalize them as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in 2013. Al-Bashir created a hornet's nest in Darfur because it was far from being a priority. If peace was to be achieved on any front, it had to be the south, with its oil reserves, whose territories finally gained independence in 2011, giving birth to South Sudan. In 2000, the first version of the so-called Black Book: Imbalance of Power & Wealth in Sudan was presented in Khartoum. It called for a social agenda to end the inequality between the central region and Darfur, which was completely marginalized. The content was not related to ethnicity or religion; they demanded to be considered citizens with rights, and there was a widespread belief that the problem was not the Darfur Arabs, whom they considered as poor as themselves, but the government. There were numerous peace attempts between the Darfur rebel groups and the government. They asked to represent the entire region, not just a particular ethnic group, to avoid diminishing their influence. They also demanded the disarmament of the Janjaweed. All was in vain. Even the intervention of the UN and the African Union in the negotiations yielded no results.

The term “terrorism” began to be used to refer to the Arabs of Darfur in general terms, a term as delicate as it was useful at the time: the context of the invasion of Iraq by the US and its allies. The Arabization of violence must be understood within the framework of the “war on terror.” Never before had there been unanimous support in the US Congress to declare genocide in any place before Darfur. The semantic debate was inevitable and, unfortunately, remains relevant today due to the current occupation and destruction in the Gaza Strip. What is genocide, what is war or war crime, and what is counterinsurgency? Iraq, Darfur, and Gaza are contradictory, the first two simultaneously, Gaza later. The law is subservient to politics and will remain a concept distinct from that of “the responsibility of the international community.” In the words of Mahmood Mamdani, also in light of the recent establishment of the International Criminal Court at the time: “Only crimes denounced by sovereign countries are real, but the aim of those in power is to transform the victims into proxies, whose dilemma would legitimize colonial intervention as a rescue mission.” It should be added that, in parallel, agreements could exist that exempted and still exempt allied and wealthy countries from complying with the law invented by ineffective organizations. Declaring genocide in Darfur could have been an opportunity for the powerful, as it implied an international obligation to intervene. Such interventions involved blaming only those they wanted to blame. The idea of impunity entered the scene, and it has not left us to this day. The real result: the population of Darfur, and that of Sudan as a whole, has been abandoned to chaos and neglect for decades.